| What's In The Box: Number Five

July 31, 2024

Box #5 will present the classic "which one of these doesn't belong?" question. That's not necessarily a good thing, as the ones that do belong don't merit much introspection.

From the second I grabbed the box, a Duraflame box, I knew I might be in trouble with more cheap mysteries. Duraflame boxes doubling as book storage boxes occurred only recently, and several of my last purging of books from the permanent collection have focused almost entirely upon mysteries, which is what we have here: 24 books in the box, 23 (relatively) cheap mysteries.

I say "relatively" because 10 of these are the nicer edition versions than the drug store cheap paperback. In addition, a few of them come from authors for whom I had high expectations. For instance, there are two B.A. Paris books ("The Therapist" and "Bring Me Back"), neither of which could quite live up to her fantastic "Behind Closed Doors." I also find "Walk The Wire" by David Baldacci, the kind of churn-them-out writer that can run hot and cold (by the way, there is another James Patterson's in this box: "Criss Cross," which I can't say rings any bells).

At least some of these mysteries ring a bell in terms of the plot: "The Chain" (cue Fleetwood Mac) by Adrian McKinty features a creepy premise where parents have to kidnap a child to have their own kidnapped child returned, a macabre pay-it-forward scheme. Sarah Pearse's "The Sanatorium" presents the "locked room" conundrum, where a storm has basically isolated a party of people at a sanatorium-converted-to-hotel. Just because I remember the basic premise of the plots doesn't necessarily mean I want to re-read these books.

So, what's the outlier? Tucked in among all of these contemporary books of murder and mayhem is Marcus Clarke's "For The Term Of His Natural Life." In some ways, it is way out of place, and in other ways, it is with its people. "For The Term Of His Natural Life" might be considered the first great piece of Australian literature, originally published in 1874. Thus, the first thing I must address is why did this one piece of Australian literature, and maybe one of the three or four most important ones I own, end up all alone in a box packed years after all of the other ones went into cold storage.

I must have finally decided I needed to concede Clarke's spot in the general fiction and literature section of our house (t.v./living room) in the last few years. It's a depressing recognition. Even though I haven't read it for probably 35 years, it still deserves prominence, along with Thomas Keneally's "The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith" as testaments to that independent study so many years ago. (Keneally's book can be found in that bookcase outside of Lincoln's bedroom, those books we wanted him to read.)

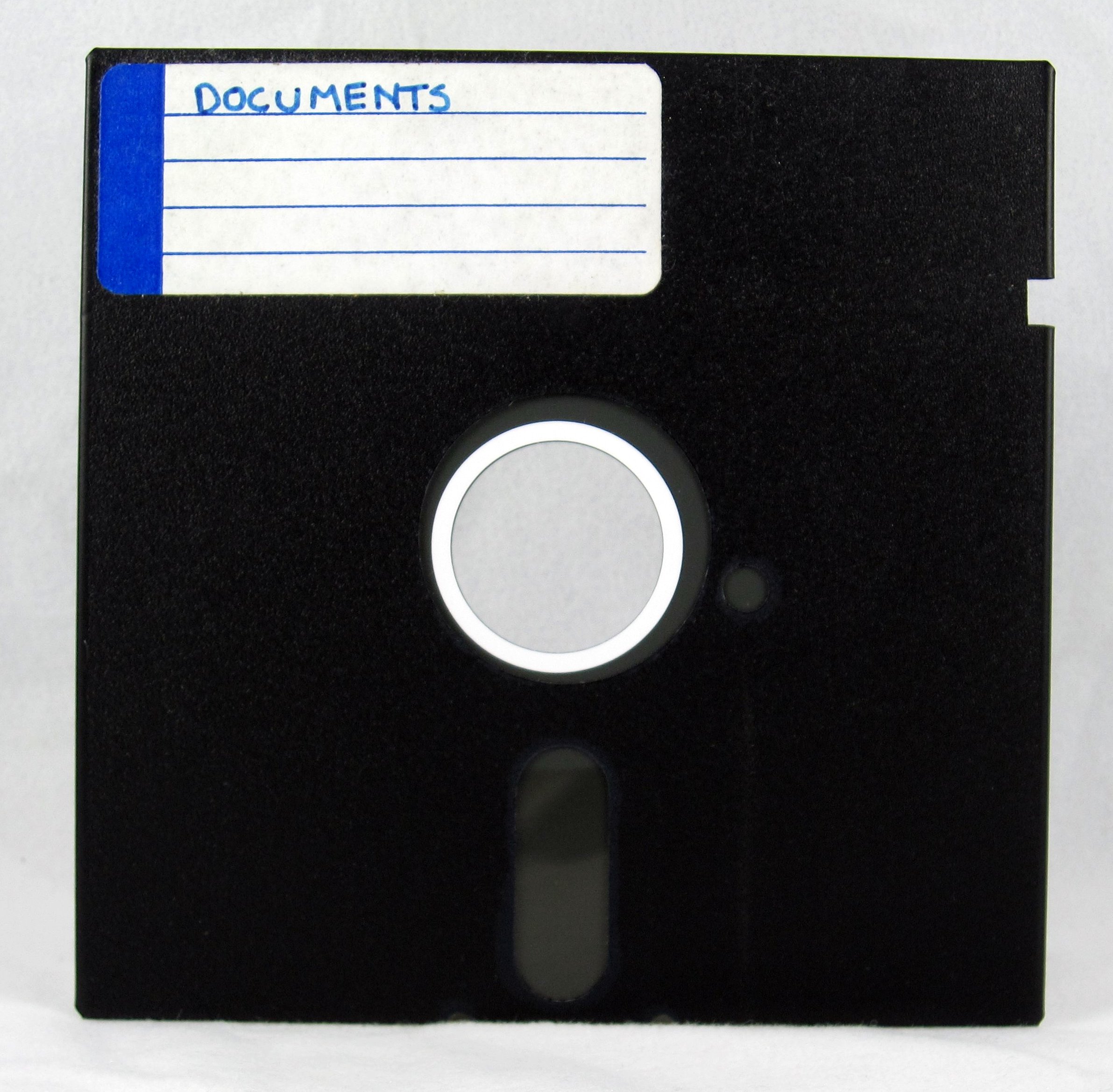

It is at this point that I wish I had copies of old coursework. I really don't remember what I wrote for that Australian Literature Independent Study at Indiana University. The paper almost certainly exists on the original floppy disc; some of us of an age (also probable owners of an Apple IIc) will remember when "floppy" actually meant something:

I found dozens of these when I was cleaning out the electronics earlier this summer (picture is not of one of mine). Who would have realized just how useless these discs would be for long-term storage?

However, to get back to the point at hand: "For The Term Of His Natural Life" is a sweeping, at times highly melodramatic, account of a convict sent to Australia in the 19th century. Rufus Dawes, the protagonist, is wrongly accused of a murder, so the novel is a painful reminder of how good often doesn't win over evil. Dawes is flogged and must flog other prisoners, presented with excruciating detail by Clarke. More than once, his freedom looks imminent, then gets yanked. One of the factors to attribute my fascination with Australian Literature was the very different origins of "first" books. American Literature, my chosen field of study, hearkens back to the dullest "origin stories," John Smith, William Bradstreet, John Winthrop, and Cotton Mather with their narrative of America "on the hill, the eyes of all people upon us," while Australian literature must grapple with the origins of a giant prison, of criminality, and they (generally) don't back away from that historical anchor.

Thus, "For The Term Of His Natural Life" is such a different narrative, even though it drips with the clichés of much British Literature from the time. More significantly, for the purposes of this reflection, the story is so difficult that anytime I ever considered re-reading it, I just couldn't bring myself to it. Like all the mysteries in the box, Clarke's book is hard to re-read, but for a much different reason.

All of this begs the question: what is the defining reason I have put so many books in storage while keeping others upstairs? The mysteries are easy to understand, but as I am seeing, many of the non-mysteries could stay alongside the "saved" books that may not ever be re-read also. I have a good friend who keeps a book journal, capturing something about each book after he has read it, which is so Dolores Fleming, I am a little freaked out. However, Dolores' son never had such diligence.

After all, after dispatching "Midnight Rambler" as a re-read from Box #1, I recently finished "How The Dead Dream," by Lydia Millet, which was pulled out of Box #2 for a re-read. The back cover summation of "How The Dead Dream" did not trigger a memory of the story, but the Village Voice blurb on the front cover ("Her funniest, most shrewdly thoughtful and touching novel") intrigued me. While I smiled a few times, "How The Dead Dream" ultimately left me thoroughly depressed. The protagonist has a series of horrible events happen to him, and he gets more deeply and deeply obsessed with animals on the brink of extinction (the cover features toy animals, which also appealed to me, reminding me of so many of my childhood toy animals). I am not sure I wanted to relive this kind of empathetic pain for a character, especially if I had rejected the re-reading about Rufus Dawes in "For The Term Of His Natural Life," which nowhere in its 150 years of publication has some reviewer cited it as "Clarke's funniest novel." His book may come back upstairs, but I am not sure I can relive the brutality described within.

Interestingly, the unintended consequence of this box review is that more books are coming back upstairs than are going downstairs. Ultimately, that is not going to work. I see a crisis looming in my future.

Full Series Here.

|