| What's In The Box: Number Eight

August 7, 2024

So, I decided to cheat a little bit and move some boxes around to get to ones deeper in the stack. I know I need something to light a spark for this series. Boy, did I find it in this old Lowe's box, which is labelled as containing, among other things, for one of my moves, a "jelly jar?" Yes, a single "jelly jar?" Honestly, I got no explanation.

In its repurposing as a book storage box, however, my little Lowe's box provides a wonderful snapshot of Dave and Pix, probably in their late 20s or early 30s. I am not saying the books were packed in the box in the early 1990s, but whatever purge this box represents, it was a shared affair for us: 26 books that I would say were hers, 25 that were mine and 5 that were shared. Given that 6 of mine are more Australian books, another one is a cheap mystery, and many of the others are graduate school books ("Long Day's Journey Into Night," "The Great Gatsby," and several on critical theory), her books definitely shine as the stars for this blog.

I could elevate the James Clavell, who she absolutely loved when she was younger, or more Heinlein, or "The Right Stuff," but these choices would still be pedestrian at best (cue Courtney Barnett). No, I direct our attention to two true treasures here, even if she turned her nose up at both of them when I brought them upstairs.

First, we have "Looking . . . Seeing: Poems and Song Lyrics by Harry Chapin!" Yeah, some dude, a Rob White, illustrated to Chapin's writings. A 1975 publication, it was done with Chapin's approval, and basic authorial byline, predating his 1981 death.

I know, readers are so jealous of Pix and me right now. Here's the kicker: it's signed by Harry. Pix says she got him to sign it when she saw him in Ft. Wayne in the mid-to-late 1970s. He apparently even kissed her, a story I refuse to ask more about, since she would have been 15 or so, and he would have been in his late 30s. I have always inferred it was more of a peck on the head, but decided life is better spent being ignorant.

You can tell Pix's emotional attachment to the signed book, given that it has been in a box that almost certainly was packed up sometime in the 1990s. I have brought it upstairs and shoved it in with the music books in the reading/music room. It is a thin, rather bent, book and if Lincoln is going to sell it someday to fund his retirement, I should straighten it out.

The other treasure is not really "Pix's book," but it was a gift clearly intended for her: "What A Young Wife Ought To Know," a 1908 publication that I am 99% sure my mother gave her around our wedding. I am about 98% sure it was a joke, and about 90% sure that Mom saw it at an antique store and bought it on a lark. Much like the Harry Chapin anecdote above, this is the historical record I intend to keep around this book.

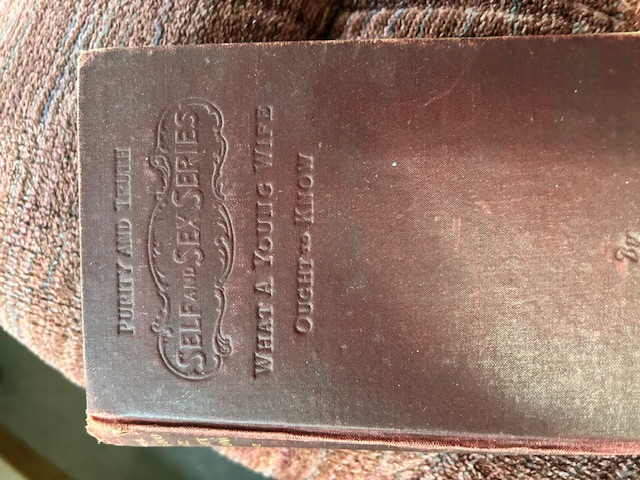

As you can see from the cover, it was part of a series:

In case you can't read that, it says “Purity And Truth," either part of, or encompassing, the "Self and Sex Series." On the inside, before we get to the text proper, we get an advertisement for "Pure Books on Avoided Subjects," which include 'What A Young Boy [or Girl] Ought To Know," "What A Young Man [or Woman] Ought To Know," "What A Young Husband [or Wife] Ought To Know," and finally, "What a Man [or Woman] Of 45 Ought To Know." (I would so love to know what was written for that rather arbitrary age.)

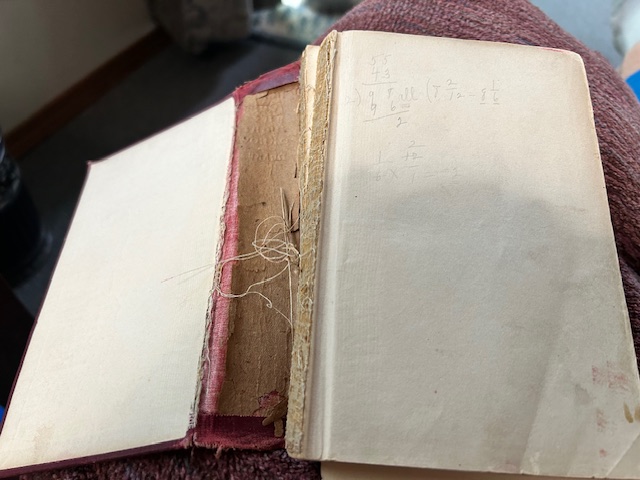

It also clearly got a lot of usage before it found the Fleming basement:

Trust me, that spine was not broken by the Flemings.

Needless to say, the book came upstairs for a more formal review, since both of us only vaguely remember it. The author, Emma Angell Drake, M.D., is afforded 11 commendations for her text before we even get to a single word she writes. These commendations, accompanied by pictures of each person, range from Margaret Sanger to Elizabeth Cady Stanton, to 5 religious leaders, to the President of Brown University, to the editor of Review of Reviews, to one other doctor, a Dr. Julie Smith. Obviously the presence of three women in this group, Sanger and Stanton, most notably, suggests that "what a young wife ought to know" might not be what your Victorian grandmother approves of. The commendations range from the sweet, as when Sanger writers "I wish every young and perplexed wife reads its pages," or when Smith encourages the book to be "part of your daughter's wedding outfit."

The men's quotes, on the other hand, suggest something less sweet, almost perverse, as when one writes about "the lasting satisfaction" that can come from the book, or when another says that "the man who sells [this book] is a missionary," or when a third praises how Dr. Drake "handles delicate matters in manner as firm as it is delicate." Really. You can't make this shit up.

So we go back to the Sanger and Stanton influences. In many ways, this could be seen as an early feminist text. Drake's preface emphasizes that "to this generation, as to no others, we are indebted for the awakening of woman." (Kate Chopin's brilliant novel "The Awakening" had been published in 1899.) Her book is segmented into 15-to-20 page chapters that cover as much about a young woman as they do about her husband or her children. The second chapter, which sounds dreadful, "Home and Dress," does a good job warning "young wives" about the dangers of corsets and high heels to their physical well-being, although her sermonizing about the importance of heredity in the first chapter is a bit painful of a read, let alone reading in greater detail in Chapter XI, "The Moral Responsibility of Parents In Heredity."

Chapter VII is what everyone is waiting for: "The Marital Relations," which furthers the sex-is-only-for-procreation argument of the Victorians. Drake's sermonizing ranges from the ridiculous ("There should be no pandering to sexual indulgence, while there is unwillingness to bear as many children, as a proper manly and womanly Christian temperance in these things will allow") to the sublime ("There is a vast amount of vital force used in the production and expenditure of the seminal fluid. Wasted as the incontinence of so many lives allows it to be, and prostituted to the simple gratification of fleshy desires, it weakens and depraves.") Are you as confused as I am? I'm tempted to ask, "come again?"

Frankly, the above diminishes my interest in reading much more, even though later chapters on "Guarding Against Secret Vice" (Chapter XXI, why does this come so late?) and "The Training Of Children" (Chapter XXII) are enticing. A Google search about Dr. Drake shows that she wrote "What A Woman of Forty-Five Ought To Know" before she wrote "What A Young Wife Ought To Know," which seems weirdly out of sequence, until I note that she was 43 when she wrote the former, 49 when she wrote the later. I think she wanted to get the autobiography out of the way. In fact, at 43 she also wrote "Maternity Without Suffering." It might be safe to say that the concerns of a young wife were not high on her priority list.

Still, this box has provided great fun for a couple of days, and I managed to go from Chapin to Chopin in one move. These are the simple gratifications of an old man.

Full series here.

|