| A Retiring Sort of Reflection

May 15, 2024

This week I retired. I am afraid the few regular readers of this website are going to get sick of hearing about that, either directly (I already have 2 or 3 songs for the song series that will be tied to retirement), or indirectly.

When I was a kid, I thought 62 was the age everyone retired. I don't know if it ever really was, but somehow as I worked my way into adulthood, I found out retirement age was usually 65 or even 67. That seemed like dirty pool, changing the playing field while in an active game. So to be retiring actually at 62 feels exactly right and, at the same time, really premature. Given that I might do some contracted-type work at this point, I guess I can say that I might have a semi-retired life. (Most of us now have that damn Third Eye Blind song in our heads. You're welcome.)

The best realization of retirement came when I had to clean out my office this week. I'm the kind of guy who personalizes an office, so it had 13+ years of Dave Fleming throughout it, and you could argue 30 years, because some items went back to my Detroit College of Business days. In the end, I left some things for SMC to chuck, realizing that in retirement much won't have the personal value for me at home (almost certainly boxed up in the basement). Pity my former, absolutely amazing, best-one-to-ever-work-for-me (cut and paste this for any job evaluations/reference letters) administrative assistant sorting through the files, especially, left behind.

I still brought back a lot, six boxes, five wall hangings, a graduation robe (never to be worn again?), and a huge model ship of my father's that he made from scratch upon retirement (if interested, see it and read more about what that represents from October 2019).

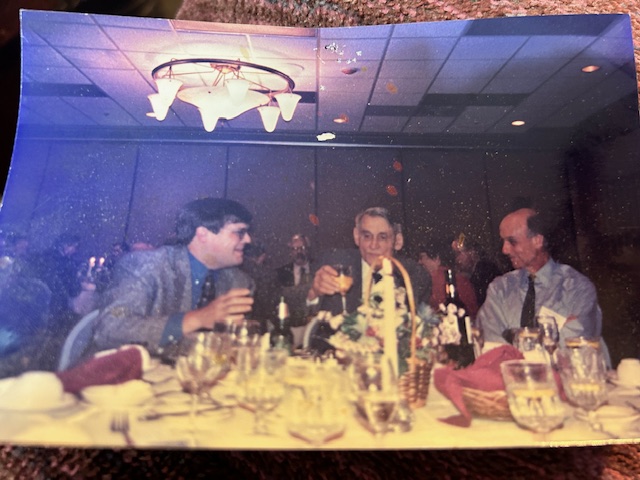

However, the most treasured "artifact" I brought back home? It could have fit in an envelope. This picture.

I know this seems pretty banal but it is a picture of me with two of my father's colleagues, talking during my father's retirement gala at West Virginia University in 1999. My father had worked at WVU thirty-nine years, thirty-five of them as the Chair of the Department of Pharmacology & Toxicology, and that celebration of his time and service to WVU represented everything that I value about a professional life. Those two men I was sitting with, Dr. Trendlenberg to my left, my father's mentor when he was a student, and Dr. Johnson to his left, one of the first pharmacologists my father mentored, were two of the most special colleagues I knew out of hundreds of special colleagues that my parents called friends.

Dr. Ulli Trendlenberg was from Germany (I have vague memories of stories of him escaping Germany during the war to do pharmacological research at Harvard, where my dad met him, but they may be false), and would come back to the United States to visit, probably guest lecture, probably do sabbaticals, and was a semi-regular part of my childhood. In the 1970s, the poor guy would be put up in my bedroom when he visited Morgantown, and after awaking the first morning in some patriotic-themed sheets (this must have been 1976), he proclaimed that he had never woken up before wrapped in the flag. He and my father were great friends, and cared for each other and each other's families in ways that were profoundly deep. How could my professional career not include such a relationship with a mentor?

Then there is Dr. Steve Johnson, the Aussie Pharmacologist, who figured so prominently in my dad's professional research. Steve, too, was a frequent visitor to our home, but because of the tie into shared research, also a frequent host for my dad, and his extended family once or twice, in Australia. He was funny, incredibly kind, and generally interested in what my sisters and I were doing growing up. He ended up showing me parts of Australia that I would never have known by being just a regular tourist. I could see that he idolized my father in a way. I delighted in hearing that accent in a late-night call that could only be Steve's. I wanted to have people I helped shape into professionals play that same kind of role with my own adult family.

By 1999, I was 37 and already the Chair of English at Detroit College of Business when this event happened. I probably had earned my place at the table beyond being Bill Fleming's son, but when I realized that I had been purposefully seated with Dr. Trendlenberg and Dr. Johnson, I felt like Charlie with his golden ticket. And while these two brilliant scientists probably would have expected to be seated next to other brilliant scientists, they both seem tickled to be seated next to the Doctor of American Literature, the adult-version of the kid with Farrah Fawcett posters and Queen albums displayed on the walls in their 1970s make-shift bed-and-breakfast. Part of why this picture makes me feel so damn good is that the moment is completely genuine. I so wish I could remember what one of us had said just before the picture was taken, but I do believe we were completely oblivious to the photographer approaching our table. Steve and I seem quite amused by something Ulli is saying.

Truth be told, if I went through my Mom's photographs from that retirement gala, I would find hundreds of people that could be versified the same way here. My parents drew professional friendships like a porch lamp draws moths. It was those kind of relationships that I wanted to build professionally, and which led me to have this picture front and center of me at my work desk. (It doesn't hurt that it just automatically makes me smile.)

I bore you all with this as a set-up for how I expected, in my younger days, my retirement to be: a massive event celebrating the tenure at one institution, planned well enough in advance that hundreds of friends, colleagues, and former students from around the world could attend. My son would be flitting between tables, having a good laugh with people I knew from WVU, maybe a few IU colleagues, a former student or two from DCB ("oh, Lincoln, you were so cuuuuuuuuuute when you were just born"), and a bunch of fellow academics, current or past, from my employer.

Life doesn't work that way anymore, and I am not bitter about it. I think my father's tenure at WVU is unheard of these days for most colleges or universities, especially in the role of a faculty administrator (straight up faculty, with the benefits of tenure, is a different story). To think I could spend 30+ years at one institution, especially once I stepped out of teaching, is a naivé illusion, and the numbers would probably show how few actually do.

I also know that retiring from much of that administrator job was very easy for my dad those last few years. If not for the research and the teaching, he probably would have retired even sooner. I remember when WVU made a change via his new dean (who had no medical sciences background) that represented everything my dad saw as the future downfall of higher education (or at least education in the medical sciences). That may have been the moment that some of the gleam went out of dad's eyes. One of the ways he and I stayed close in his post-retirement was with me calling him to tell him something outrageous about my professional world, and he would listen, provide whatever opinion he could, but ultimately sigh. "I got out in time. I am glad I am not having to deal with that."

Maybe that's why my parents (or whomever did table assignments) put me between the Australian and the German. I wouldn't hear any of the grumblings about the American higher education system that probably many of them felt like my father. I should look at that smile in that picture and see the innocence that is there.

So, maybe I can't have a big wingding. Maybe I can accept the incredible out-flowing of love, caring and respect that comes from a well-timed FB post (honestly, for awhile, I didn't think they would ever stop coming in). Via texts, emails, and other written notes, I have testaments to my impact that are easily retrievable, that aren't subject to the vagaries of time and memory. Maybe it's all for the best, especially if my father's words are now my words: "I got out in time."

|