| Artifacts and Academics: The Sea Cloud

October 23, 2019

Today, I start a series of blogs that I'd originally planned for another venue, or at least to be shared with another venue. With that venue shut down, I will present it solely through this website. Not sure yet the regularity of the series, but I will call it "Artifacts and Academics," intending to reveal how some of the artifacts of my life can speak to the enduring value of lifelong learning. It is common to metaphorically shed our possessions in our trek to seek some kind of higher spiritual state. I lean more toward the sage wisdom of Glenn O'Brien who said, "if you don't have heirlooms, you're not living right. To live well, one must have a past and a future."

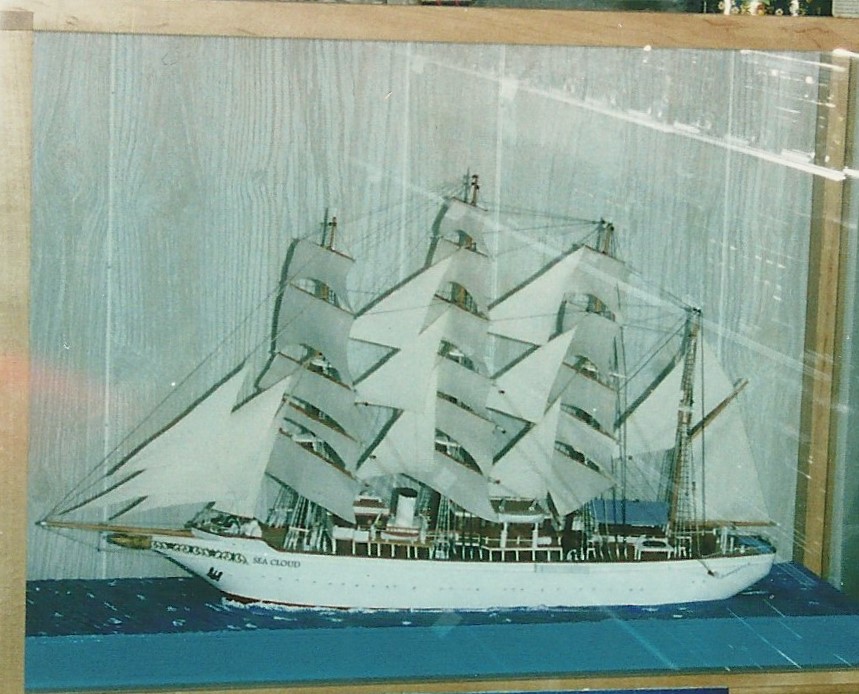

I start the series with a ship, a model of The Sea Cloud.

This model sits on top of my bookshelves at work in a magnificent case, both ship and case built from scratch by my father during his retirement. Whenever I have to exit my office for good, moving it will be a chore, much like getting it into my office was a chore. However, it was worth it and remains worth it because I am daily reminded of the entwining of vocation, vacation, and fascination.

You see, The Sea Cloud was a schooner built in 1931 as a replica of a classic sailing ship, used by Harvard University and their Friends of the Museum of Comparative Zoology for special study tours (at least of the Caribbean and Mediterranean Seas). In 1993, my father, Harvard grad, received a flyer to participate in a 10-day Caribbean "study tour" on The Sea Cloud. My mother slightly twisted my father's arm to do it (it meant he had to sacrifice time at a national conference he valued very much) and he signed on.

Recognize that my father's vocation was Chairman of Pharmacology, and yet he jumped at a "work tour" on a sailing ship that would involve study outside of his direct profession. At the time, even though I was 31, I was a little befuddled by this notion of a "tour of the Caribbean" that would resemble nothing like a Carnival cruise. Whatever Dad took from the "vocation" (I know he had three or four traveling lecturers), most of it is forgotten in light of his vacation and fascination with the ship. I believe he had to work on the ship during his ten-day cruise, although I am now willing to accept that he was less likely to hoist the main sail than to perhaps pick up a microscope slide.

My mother, ever the historian, has captured the ship's refurbishment in her journals (foreshadowing of a future submission within this series): She writes that recently "the Sea Cloud had . . . been completely refurbished retaining much of the original elegance, including paneling, carved ceilings, dining rooms, owners’ bedrooms, and many original staterooms and oil paintings. Its four masts and '29' (Bill counted 30) sails made it one of the most graceful ships. Furthermore, it would not be crowded as it only took 70 passengers. Bill managed to get one of the staterooms that was priced for a single person although it had a lower bed and upper berth. It turned out to be perfect because it was on the Upper Deck with a door that opened directly onto the deck."

I get great pleasure in visualizing my father as a highly functional Raymond Babbitt, feeling the need to correct the sail count: "30. I counted them. There are 30 sails, not 29." It is a testament to his attention to detail that he counted to correction (and a testament to Mom's sense of historical accuracy to include the parenthetical).

Dad's fascination with the ship began the day he stepped on it, determined (again, according to Mom's journals) "to have a model of it. I [Bill] discovered that the ship company offered a model already constructed, for $6,000. Not only was that an enormous sum, but, having been a pretty capable model builder in my younger days, I could not have a ship model built by someone else! Since no kit was available, I would have to build one from 'scratch.' Although I had never done such before, I had built some very complicated ship models, but none after the age of 25." Dad would be 68 when he would set off on his second life as model builder.

That's because his construction of the model wouldn't begin until after he was retired. In 2000, less than a year after his retirement, he took my mother with him on a second "work tour" on The Sea Cloud. I am sure he sold it to her (not that she needed much arm-twisting) as a great experience and vacation. Trust me, if I had a problem seeing my father as a crusty sailor working the boom, it was even harder to picture my mother swabbing the decks. Dad was probably measuring poop decks, while Mom was chatting up the staff about the cabin conditions, which she later described as superior to some on the "cruise" ships they had taken.

Thus, in 2001, Dad turned his fascination into the construction of the ship model from scratch. The end result, a model measuring probably 3 feet in length, in a gorgeous glass display case, is what I gaze upon everyday for inspiration. It represents all the intellectual and creative qualities that my father bequeathed to his family, friends, students and colleagues through his years of employment (I can't say working years because he worked, a lot, on this model).

There are many things I never got from my dad, most significantly the pleasure of building models. Frankly, as a kid I sucked at model building, and I would have a kit, poorly written instructions, and a doting father who would have loved to assist if I let him. In this case Dad started with about 100 photographs, some drawings and measurements from when he was on board, and some brochures. I look at the finish product with so many questions based upon my experiences:

Did he not come unglued as the glue adhered his finger to the forestay?

As he constructed the hull, did he not feel betrayed by the board that didn't respond as he hoped?

Did the mizzenmast make him miserable as he missed its mark?

The Sea Cloud model cast my father into a retirement vocation: model ship builder. After reconstructing The Sea Cloud, he proceeded to construct dozens of World War II ships and boats, all from scratch. His basement, once the show ground of his pre-retirement fascination with model trains had now become trains and ships, sprinkled with his books, especially focused on baseball and military history. His fascinations were all encompassing.

Everyday as I go into my office, I see the model and I am reminded how it says everything I need to remember about my father: his love of science, his passion for creating things, his focus on what he most wanted to do. I hope to leave the same for my son. Let's hope he figures out how to display thousands of random writings.

|