| Artifacts & Academics: Paper

November 24, 2019

"Hold on, hold on to that paper," David Byrne and the Talking Heads* told me many years ago. Oh, how I have taken them at their word. For years, I have looked at the reams of papers in my basement, desks (both office and home, which has multiple desks), filing cabinets (again both home and work) and boxes, trying to motivate myself to shred, burn, or simply recycle. I used to think I just couldn't do it, and that it would be Lincoln's onus to deal with it.

Any concern I had that I was a pack rat in general has been lessened this week. I resigned my position with the county's planning commission after 6+ years of service, including over 3 years as its secretary. Simply put, I felt I couldn't give the commission any time with a lot of other things on my plate. I also have to admit that even after 6+ years, I never warmed to the responsibility. Reviewing master plans, debating zoning ordinances, and approving property requests numb the mind even on a good day (mind you, this comes from a guy who sits through meetings for a living). Local government is someone else's fate in life!

Thus, this week, after my last meeting, I found it surprisingly easy to start purging my office of 6 years of documents related to the planning commission. Hundreds of pages of easement restrictions, of "adult use" definitions (see "What You Zone" from July 2016), of crude hand-drawn maps to show property, of township meeting minutes, of land use applications, of legal opinions: In all these cases, I heeded Byrne's additional advice to "go ahead and rip it up, rip up the paper." Not sure I could shred some of it quickly enough.

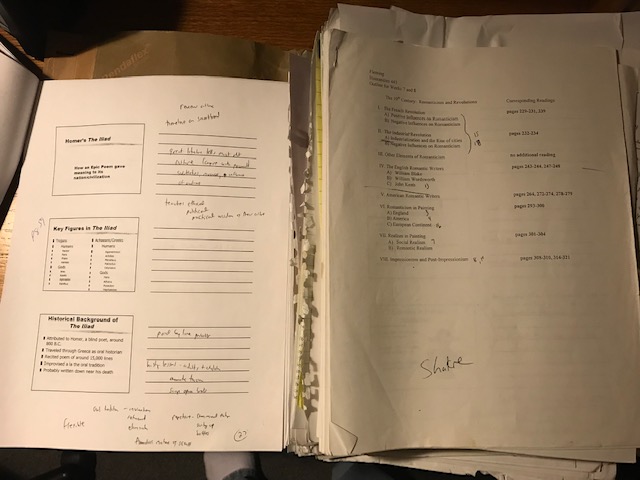

This weekend, however, as I headed down to the basement to confront my personal paper tigers, confident I could begin a real cleansing, I immediately got stuck with the "what if?" scenarios. In a box that I haven't explored for years, I found huge files of lecture notes, outlines, transparencies, review guides, exams, assignment instructions, syllabi for Western Civilization I and II courses that I taught at Detroit College of Business (DCB) and Davenport University (the materials appear to date to around 2003 and earlier).

In addition to those two over-filled folders, I found a folder of personal items from my time especially at DCB: my initial resume and letter; evaluations of my teaching; recommendations letters from colleagues; my letter of disappointment at a tenure decision and the corresponding letter from administration.

In the end, my scrummaging through these boxes of old papers resulted in my shredding about 20 random pieces of paper, but nothing from this box. Why can't I let this stuff go?

The specific career stuff seems understandable. I am enough of Dolores Fleming's son to know that such personal history has value. Who knows, maybe Lincoln one day will look at these and chuckle at the professional who lurked behind the man who responded, "I'm David, pleased to meet you," every time he said "I'm bored" or "I'm hungry"; or, when asked if something was possible, always replied "Kim Possible?"

It's the inability to pitch former teaching materials that puzzle me. While they offer a little bit of personal history, it is much too nuanced to be of interest. Why did Fleming focus on Caravaggio's "Conversion of St. Paul" instead of his "Death of the Virgin"? Why did he seem obsessed by the dichotomy of castle versus cathedral through the Middle Ages? How did anyone read his handwriting? Ultimately, pretty boring questions.

I am only saving these because somewhere in my mind I am afraid I may need to use them again. It's a ridiculous thought. For one thing, I don't have any idea where all of these materials were saved electronically (something much newer than the original floppy disc, but much older than a flash drive). I would have to transcribe almost every word. And a school's IT department would probably howl at me when I told them I needed an overhead projector for transparencies. Secondly, and more sobering, is the fact that the odds of me teaching Introduction to Western Civilizations, I or II, again are astronomical. I probably was never even appropriately credentialed to teach the course 20 years ago.

Nevertheless, I hold onto these materials. I think most academics understand this. The way we carefully put together our materials for classes is our art, and we maintain those as a lifeline to whenever we suddenly have to teach those classes again. Would anyone ask Picasso to re-do "Guernica" decades later? (O.k. maybe a Fascist government would demand that.)

In the end, academics are defined by our "papers" (often with the same snobbery as others may have regarding their peerage or their dog's lineage). If someone were forcibly to take away these materials, they'd be taking away our souls.

So if one David wrote "Paper," this David counters with "Papers."

Papers

"Show me your papers,"

Patched tweed-suited men ask of me.

I allow them to peer in the box,

Nudging my words around

With their fat fingers,

Ashes dropping from pretentious pipes.

"Don't take my papers," I plead.

"I am nothing

If not my arcane lectures,

Dated drafts, yellowed notes."

I don't dare admit

I roll with my papers,

Between the sheets,

In hopes they might

Conceal my conceit.

My attachment may be a tad

Eccentric, even grotesque,

But when I'm old and tired

And beaten to a pulp,

They will be the security I need.

They will vouch that I was no fraud,

No brevet extended for my rank

Or temporary authority.

They'll be my final declaration,

My resolution to hold on tight

To the reclamation of my past.

Yet, to the men so commissioned,

I simply plead,

"Don't take my papers."

* Talking Heads. Paper. Fear of Music. 1979

|